“It is not important to see different places with the same eyes, as much as it is important to see the same places with different eyes.” Lucio Anneo Seneca

Try and ask to at least 5 people, even without knowing them: “Would you change something about your life? Would you change something about yourself?” What do you imagine you would receive as an answer?

Change fascinates everyone, only a few will answer with a blunt “no”. Wait another few moments before letting go your interlocutor on his way, and ask again: “When will you do it?” At that point the answers will be much more varied, between an “I don’t know…we’ll see” and a “When it’ll be the moment”, shielded behind a “It’s not up to me” and a “If only I was younger… had the time… had the money I’d do it.”

Let’s come to the point: to desire to change it’s not enough to change. Actually, not even deciding to change is enough to do it for real! The concept of change is much more complex than it seems and we know from experience that being able to transform a behavior or a situation implies much more energies and efforts than its simple intention. Let us try to examine in depth the subject to find some starting points for action, and to increase the awareness regarding what we can do to live fully the little and big changes inside our growing path.

Which change are we talking about?

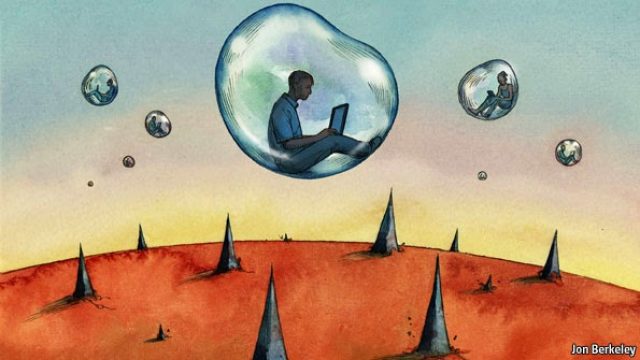

Trying to reduce as much as possible, we can identify two types of change: occasional and intentional. The first one is a form of adaptive response, sometimes unaware, to the environment that, as we have written, changes constantly. On the occasional change in itself doesn’t necessary depend an aware growth of the person: in other words, we can even not notice that we are changing inside a situation that is in constant mutation. In this sense we speak of adaptive response.

What happens when we realize that things are changing?

At this point two scenarios open, depending on how much responsibility we choose to take inside the change, on how much control we think we have. A first scenario brings us to think that this change doesn’t depend on us, though we will be inevitably affected by it: attributing the responsibility of the change to the outside, we try to resist it, and we strongly anchor to our vision of the world that, in fact, excludes it. James Rotter in 1966 has been the first to talk about “locus of control”, distinguishing people between those that position this psychological point of control outside or inside themselves. Inside a changing process, putting outside the point of control means to consider somebody else or something else responsible for its activation and management, by doing so the person develops a sense of frustration and powerlessness, living the change as an imposition to contrast or to which, in the end, passively submit to. Just like Nanetti (1999) observed “Those who entrust their happiness to misleading changes, in the magical certainty that every problem will be solved turning the page, or waiting for the change of others, are in fact feeding their own suffering”.

In a second scenario, putting the point of control inside means to consider the change depending on ourselves (at least in part), feeling responsibly involved in the actions to be done to take the best out of the process. This certainty of effectiveness and of being able to provide an active contribution, transforms an occasional change in an intentional change, the second type of change we had introduced. I underline the words “certainty of effectiveness”: the important, in fact, is not the effective control of the change, it is the psychological perception of being able to affect it. To change intentionally, then, doesn’t just mean to follow the trail of change: it means to give ourselves the possibility to transform the way we see ourselves, experiences, contexts, reality itself.

What do we need at this point to activate an aware transformation?

- Motivation: let’s clarify to ourselves exactly the reason that pushes us to go towards a situation or to distance ourselves from another. Let’s define a purpose of change (for an in-depth analysis read: How to transform the good intentions in purposes)

- Decision:the awareness of wanting to do something sacrificing something else. Transforming, in fact, we will have to give up a few habits, someone, something, just like the butterfly gives up the cocoon to unfold its new wings. The decision also depends on the importance that we attribute to the change. Without leaving something behind, we can’t reach something else.

- Creation:let’s plan the change starting from the first useful action that we can do, let’s give ourselves some deadlines, let’s identify some parameters to verify our progresses.

- Consolidation: let’s get used to celebrating our results, let’s go looking for the positive evidences of the change, sharing them with who is able to appreciate us.

Which mental traps (Prochaska, 1999), which destructive thoughts can we meet during our transformation?

– I can’t do it: this thought appears when the change touches sides of oneself that are not yet completely aware, and is accompanied by the temptation to attribute the responsibility of the change to the outside (external locus of control). To contrast this thought let’s ask ourselves what can we do instead, even a small thing to continue the change.

– I won’t do it: it is another way to tell ourselves that we are not willing to give up the benefits of the situation as it is. It’s easy to run into this thought when the advantages of the problematic situation are considered bigger or comparable to the costs connected to it, or when you would renounce to immediate benefits in view of long-term advantages. Are we really willing to not change to enjoy the present benefits? In that case we can’t complain or grow frustrated because we consciously choose to resist the change. What, instead, are we willing to lose to increase our awareness? Are we willing to work hard to evolve?

– I don’t know how to do it: it is the perception of not having enough instruments to operate the change. Who can help us in the transformation? To whom will we ask for support?

So, which is your next transformation?

“Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t – you’re right.” H. Ford